It was at this day, one year ago, that my dad died.

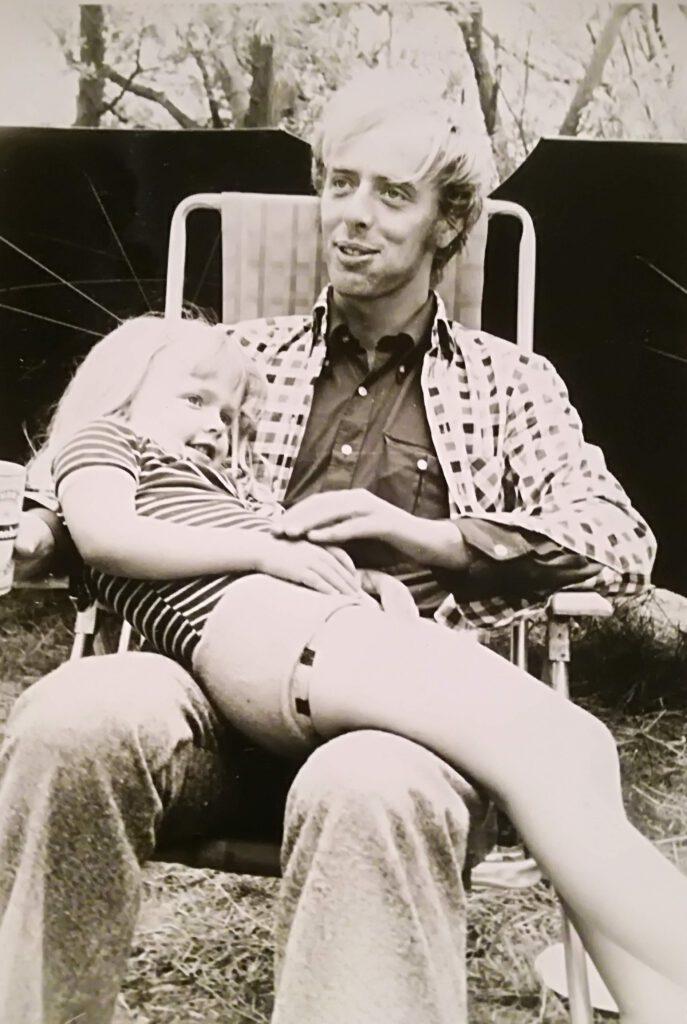

He lay in his bed in the living room, so he could still look out over his beautiful, landscaped and hand-shaped garden — the one he had maintained so carefully. He loved those trees as much as he hated them (because of the falling leaves). Firm wooden colossuses, standing tall and proud, unaffected by wind, hail, rain, thunder, or even the blistering sun. Just like he had once been — a strong tree himself, with an owl perched on a branch for wisdom, or a dove for clumsy drollness. My dad could be a wise man, just as easily as he could be funny or foolish. He knew those trees better than he ever knew his children.

That had been different.

Growing up, I don’t think he ever worked in the garden. I remember that one time he pruned the pussy willow in the front yard, at my mother’s request. After proudly reporting the task was done, she rushed outside — only to find that he had expertly trimmed away every single hanging willow branch. All that remained were wild, upright stalks, as if the tree had been electrocuted. We teased him about it for years.

But that garden? That was different. He loved it. I’m sure that if I went there now and he were still alive, I’d find him on his skinny-boned ass, pulling up weeds. I love that image in my head.

It was at this day, one year ago, that my dad died.

It was Father’s Day.

A few days before, my brother had called to tell me our father was in the hospital. Terminally ill. When I asked if I could come say goodbye with my son, he answered: “As long as you don’t make a drama.” That wasn’t a boundary — that was an accusation. A warning. It cast me and Mec outside the situation, as if we were a risk. Not family. As if we had to bow to someone else’s pain, while our own didn’t count. You excluded us. And with that, you excluded Mec and even worse ‘you excluded him too. That wasn’t neutral. That was a choice. And choices have consequences, instead we were constantly concerned with ‘not being too much’ and taking other people’s feelings into account. Choosing our moments, weighing our words, moving without being visible.

One being: my dad died on Father’s Day, without his daughter or grandson at his side.

And I believe that, too, was a choice.

It was at this day, one year ago, that my dad died.

I came in to say goodbye to the man I immensely loved — and always struggled with.

The memory of him lying there is still painfully vivid. And I’ll tell you: it wasn’t pretty. I touched his hand for the last time — those hands that had done so much work. That had carried me, literally and figuratively — but had also pulled away from me so many times. The same hands that helped me out of the mud. That rebuilt my fence after storm Dennis. That were there when I fell down thirteen steps. I miss those hands. I miss him.

After that unbearable visit, I fled my parental home.

To the Lambertus church.

In search of peace.

It was a Father’s Day mass. I slid into the pews with Mec, trying to come back to myself. That church — where my father had once organized jazz services, combining sacred with pub-style joy. Where gospel rang through the nave. A thorn in the side of the minister — who embraced it anyway.

I was back there again this past Saturday.

It was one year to the day since I learned he would die.

It was dark outside. The church was full. Colored lights and smoke danced through the old Gothic space, designed by Pierre Cuypers. Then the first notes of Who Wants to Live Forever filled the air — Queen, unplugged. Goosebumps. Tears at the edge of my eyes. For a moment, we were together again. You and I. Right there. In that music. In that space.

The band proudly announced theirs was the first of many musical performances in that church.

It was at this day, one year ago, that my dad died. It was Father’s Day.

So yesterday, I celebrated Father’s Day in the place where I feel closest to you: De Noordkade, at De Afzakkerij.

And you were there — so present. (As was mom.)

Like those tall trees, you appeared on the gigantic silos — standing proud.

De Noordkade was your second home.

Your birthplace was just across the water.

Of course, your life had always revolved around that canal.

As a young man, you worked at Driessen. My grandfather’s cattle feed factory stood there.

You grew up there. You later started your own company there.

And we welded your name onto that silo — because you once told me how you remembered the ticking sound they made at night. How you couldn’t sleep without it.

Those sounds comforted you then — just like seeing your name there comforts me now.

You loved De Noordkade. You loved talking to Stefan — he was like a son to you — and you were proud of everything he had built.

You felt useful there. Valued. Needed.

You needed that recognition, that sense of being part of something.

And those young men? They loved having you around — even if sometimes I’m sure they were quietly glad when you finally left again.

And yesterday, when I walked out of the bar, you left too (hands in hands with the sun)

Just like you did one year ago.

Look closely and see Betty & Ton on the silos

I don’t care what others think, Dad.

I love you.

And I miss you.

Deeply.

Forever your only daughter.